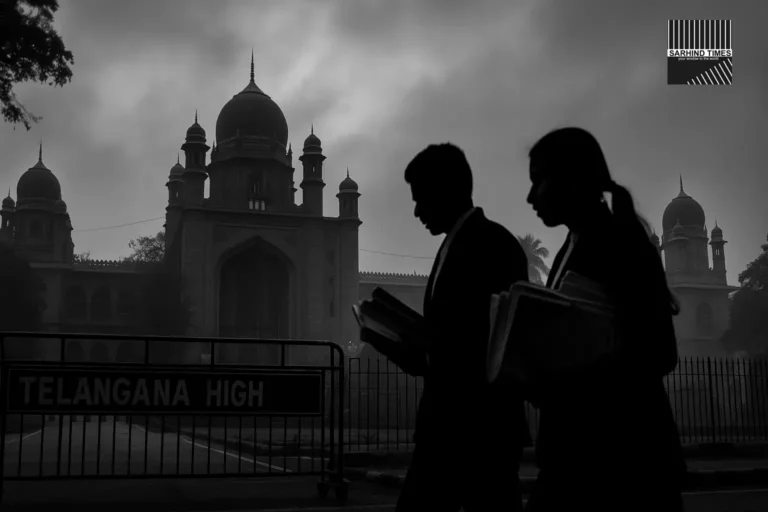

The apex court has sought a detailed status report from the Union Government within four weeks, reigniting the national debate on personal laws, equality, and secularism.

In a development that could reshape India’s legal landscape, the Supreme Court on Thursday directed the Union Government to submit an affidavit outlining steps taken toward introducing a Uniform Civil Code (UCC). The directive revives a constitutional conversation dormant for decades but central to the nation’s idea of equality before law.

The Order: Four Weeks to Clarify the Roadmap

New Delhi, October 24 – A bench of Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice Sanjiv Khanna, and Justice Bela M. Trivedi on Thursday asked the Ministry of Law and Justice to clarify, within four weeks, the Centre’s position on framing a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) applicable to all citizens irrespective of religion, gender, or region. The court was hearing a clutch of petitions — some demanding expeditious UCC implementation under Article 44 of the Constitution, others urging restraint to preserve personal-law autonomy.

“The Constitution envisions a UCC as an aspirational goal, but its realisation must follow democratic consultation. Since the Union Law Commission has concluded public hearings, we seek the Centre’s affidavit on follow-up action.” — Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud

While declining to dictate policy contours, the bench underscored the need for institutional clarity after extensive public consultations by the Law Commission. The affidavit, it said, should disclose concrete steps and timelines for any proposed reforms or legislative drafts.

Background: The Constitutional Context

Article 44 of the Directive Principles of State Policy exhorts the State to endeavour to secure a uniform civil code throughout India. Yet, seven decades after Independence, personal laws governing marriage, divorce, maintenance, adoption, and succession remain religion-specific — from the Hindu Code Bills to Muslim personal law, the Christian Marriage Act, and Parsi succession regimes. Reform attempts have arisen in cycles, from Nehru-era codification in the 1950s to Law Commission explorations in the 2000s and again in 2023–24, when citizens were asked whether “uniformity” should imply a single statute or a harmonised set of principles that guarantee equality and choice.

Unlike fundamental rights, Directive Principles are non-justiciable; courts cannot compel Parliament to legislate. However, successive judgments have nudged governments to consider reforms that promote gender justice and legal certainty while respecting religious freedom.

What the Court Asked For

The bench issued a structured set of queries to the Union Government, seeking transparency on method and milestones rather than a rushed, one-size-fits-all statute.

- Status of consultations with states, religious bodies, civil society groups, and legal experts.

- Any legislative or policy proposals prepared so far, including white papers or draft frameworks.

- Timelines and mechanisms for placing proposals before Parliament or a parliamentary committee.

- Interim steps undertaken to improve gender justice and due process within existing personal laws.

“The issue requires balancing fundamental rights with religious freedom. Government is studying comparative models to avoid adversarial narratives.” — Solicitor General Tushar Mehta

Political Reactions: Reform or Polarisation?

The directive triggered immediate political reactions. Leaders of the ruling party framed it as a long-pending reform advancing gender justice and legal clarity. Opposition voices warned against conflating uniformity with national unity, urging granular consultations to protect minority and regional customs.

“Our goal is gender justice and legal clarity. A UCC will emerge through dialogue, not decree.” — Arjun Meghwal, Union Law Minister

“India’s diversity is its strength. Uniformity must not be confused with unity.” — Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament

Regional parties from the Northeast and southern states cautioned that customary tribal practices and matrilineal traditions should not be overridden, and that any national framework must include carve-outs or opt-in models sensitive to local contexts.

Legal Voices: Between Judicial Nudge and Parliamentary Primacy

Senior jurists welcomed the court’s focus on process while reiterating that the shape of a civil code remains a legislative choice.

“Courts can nudge but cannot draft codes. UCC is a policy choice to be debated in Parliament.” — Mukul Rohatgi, Former Attorney General of India

“Instead of one giant statute, we could harmonise principles — equal inheritance, consent in marriage — across personal laws.” — Prof. Faizan Mustafa, Constitutional Expert

Societal Perspectives: Equality, Identity, and Trust

Women’s organisations view the order as an opportunity to modernise discriminatory provisions. Religious groups urge dialogue over imposition, emphasising that personal laws intersect with identity and faith practices protected by Article 25.

“Uniformity should not erase identity, but it must guarantee equality. Laws that discriminate against women have no religion.” — Rekha Sharma, President, All India Women’s Conference

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board signalled plans to intervene, stressing that any reform must arise from consensus-building and constitutional safeguards for religious freedom.

Historical Echoes: Shah Bano to Sarla Mudgal

Debate over a common civil framework has recurred at pivotal moments. In 1985, the Supreme Court’s decision in the Shah Bano case expanded alimony rights under secular law, prompting legislative reversal in deference to religious autonomy. In 1995, Sarla Mudgal highlighted how disparate personal laws can foster legal uncertainty and forum shopping, urging Parliament to consider a uniform framework consistent with constitutional ideals. Since then, courts have advocated incremental harmonisation — modernising specific inequities while urging deliberative politics for broader change.

Constitutional Debate: Equality vs Autonomy

At stake is a delicate balance between Articles 14 and 15 (equality and non-discrimination) and Articles 25–28 (freedom of religion). Advocates of a UCC argue that a citizen’s civil rights should not depend on religious affiliation. Opponents caution that erasing personal-law diversity could erode cultural pluralism and deepen mistrust. A converging view proposes a middle path: harmonised principles guaranteeing equal rights and procedural fairness without flattening all rituals or customs into a single template.

“True uniformity is about equal rights, not identical rituals. The challenge is to build consensus, not conformity.” — Dr Gauri Pillai, Constitutional Scholar

Regional Complexities and Goa’s Example

Goa applies a common civil code derived from Portuguese-era law, covering marriage, succession, and guardianship across faiths. Elsewhere, practices vary widely — from tribal councils in Nagaland to matrilineal inheritance patterns in parts of Kerala and Meghalaya. Any national framework will need calibrated mechanisms: model codes, state-level adaptations, opt-in systems, and respect for constitutionally protected customs.

Global Models: One Size Rarely Fits All

Comparative experiences range from Turkey’s secular, Swiss-inspired civil code to Indonesia’s dual-track system of religious family law alongside common property statutes. Multi-faith democracies often evolve blended approaches: secular baselines on equality and consent, with space for faith-based rites that do not infringe fundamental rights. India’s path will likely combine universal rights with procedural flexibility and robust judicial review.

Public Sentiment: More Support With Conditions

Recent polling suggests conditional support for a UCC when framed around gender equality and due process rather than cultural uniformity. Urban youth and women register higher approval, while rural respondents express indifference or concern about disruption to local practices.

| Indicator | Finding (2025) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Urban support for UCC | 58% favor if consensus and equality ensured | Framing matters; equality-first narratives gain traction |

| Strong opposition | ~30% oppose outright | Identity concerns and fear of central overreach persist |

| Youth sentiment (18–35) | Higher support relative to older cohorts | Reform appetite linked to economic mobility and gender justice |

Law Commission and the Consultation Track

The Law Commission’s 2023–24 exercise gathered submissions from religious bodies, jurists, activists, and ordinary citizens. Themes that emerged include the need to equalise inheritance rights, guarantee consent and minimum age in marriage, and ensure due process in divorce and adoption. The Commission also explored whether to codify a baseline of rights while allowing rites and ceremonies to remain faith-specific, provided they do not violate constitutional guarantees.

Economy, Administration, and Ease of Living

Uniform or harmonised family laws could reduce litigation, simplify succession planning, and clarify rights in family-owned enterprises. A predictable legal environment lowers transaction costs, benefiting MSMEs and startups that rely on clear property and guardianship rules. However, administrative transition must be paced to prevent service disruptions in registration, revenue, and court processes.

Risks and Safeguards

- Perceived majoritarianism if reforms are seen as targeting a single community.

- Loss of trust if consultations are perfunctory or opaque.

- Implementation gaps across states with varying administrative capacity.

- Judicial overload if transition generates a spike in disputes.

Mitigation measures include transparent white papers, phased rollouts, state-level adaptation windows, independent gender and minority impact assessments, and legal aid to support vulnerable litigants during transition.

Expert Voices

“Uniformity is not the enemy of freedom. It is the instrument of fairness.” — Justice Leila Seth (retd.), archived remarks

“Faith can coexist with modern law if dialogue is respectful.” — Dr Hilal Naqvi, Islamic Scholar

“The UCC must begin with women’s property and succession rights — these are non-negotiable.” — Indu Malhotra, Former Supreme Court Judge

Implementation Options: From Model Code to Modular Reform

Policy designers outline three broad pathways:

- Comprehensive Code: A single civil statute covering marriage, divorce, adoption, maintenance, and succession nationwide.

- Model UCC: A template law passed by Parliament for states to adopt with state-specific schedules protecting distinct customs.

- Modular Harmonisation: Amendments across existing personal laws to equalise rights on key issues (age, consent, property), with an eventual convergence into a unified framework.

Each pathway carries trade-offs in speed, legitimacy, and administrative complexity. A hybrid approach could start with modular equalisation and evolve toward a model code as consensus deepens.

Timeline: From Affidavit to Possible Legislation

| Phase | Date/Year | Milestone |

|---|---|---|

| I | By Nov 21, 2025 | Centre files affidavit on consultations, proposals, and timelines |

| II | Dec 2025 – Feb 2026 | Supreme Court reviews affidavit; possible expert panel for monitoring and follow-up |

| III | Budget Session 2026 | Potential tabling of a White Paper on Civil Law Reforms; committee scrutiny begins |

Next Steps: Clarity Over Compulsion

The Supreme Court’s order does not compel a UCC; it compels a status report. If the affidavit reflects substantive progress and a feasible pathway, the court may close monitoring with observations, leaving the political heavy lifting to Parliament. If gaps persist, it could ask for periodic updates or constitute a limited expert body to track gender-justice reforms pending legislative action.

Bottom Line: Between Dream and Debate

The judiciary has reopened a constitutional conversation at the heart of India’s republic: can a common civil language of rights coexist with a mosaic of faiths and customs? The answer will not emerge from a gavel’s strike alone, but from patient statecraft. Whether India adopts a universal code or a harmonised patchwork, the legitimacy of the outcome will depend on empathy in consultation, clarity in drafting, and fairness in enforcement.

“Reforms without empathy breed resistance.” — Dr Nandini Menon, Sociologist, JNU

For now, India stands at a familiar crossroads — a civilisation of many faiths seeking to be a republic of one law. The court has asked the question. The answer rests with Parliament and the people.

+ There are no comments

Add yours