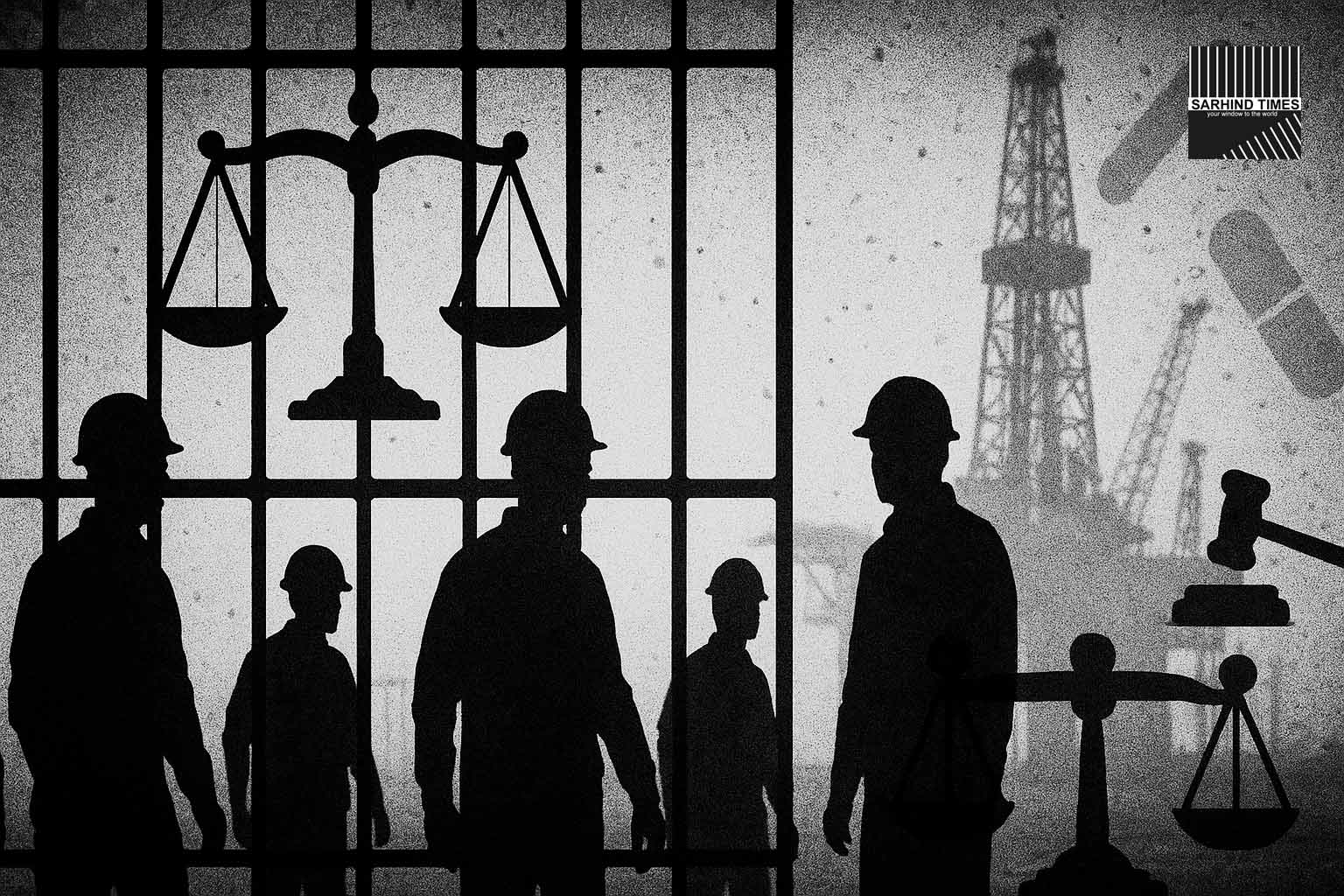

Dehradun / New Delhi, October 18, 2025 — In a decision with potentially sweeping implications for public sector employment, the Uttarakhand High Court has struck down a 1994 central government notification that prohibited the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) from engaging contract workers. The court held that the notification was invalid because it violated Section 10(2) of the Contract Labour (Regulation & Abolition) Act, 1970, having been issued without required consultation with the Central Advisory Contract Labour Board.

Justice Pankaj Purohit, presiding over the case, observed that the government’s process was flawed: the ban was grounded in a subcommittee report that inspected only 4 of ONGC’s 34 units nationwide, and no record existed to show that the Advisory Board had approved or even considered that report.

The judgment effectively lifts a three-decade restriction on ONGC’s ability to engage contract labour, and sets a precedent for other PSUs facing similar constraints. Government, labour unions, and corporate stakeholders are now closely watching how staffing, outsourcing, and labor policies will be recalibrated.

Historical Context & The 1994 Notification

Why the Ban Was Imposed

Back in September 1994, the central government issued a notification barring ONGC from employing contract workers in 13 categories of operations, effectively mandating in-house regularization. The rationale was to ensure direct employment in sensitive or core operations, especially in energy and strategic sectors.

This direction had become entrenched over decades, influencing staffing models and labor practices in ONGC and similar PSUs. Some units that had been operating with outsourced staff either internalized them or avoided contract hires in those roles.

Legal Challenges Through the Years

ONGC long contested the ban. The company argued that the notification was based on shallow fact-finding, procedural lapses, and that the government bypassed the statutorily mandated advisory consultation. The matter had simmered in courts over the years.

Labour unions and some regulatory defenders countered that the ban was essential to protect job security, prevent exploitation, and maintain oversight in critical operations. Over time, this standoff contributed to bottlenecks in outsourcing flexibility in PSUs.

The High Court’s Reasoning & Legal Principle

Mandate of Section 10(2) is Mandatory

The court underscored that Section 10(2) of the Contract Labour Act mandates consultation with the Central Advisory Board before any notification abolishing contract labour in any establishment is issued. The court held that skipping this statutory step is fatal to the validity of the notification.

By citing precedent and constitutional interpretation, the bench reaffirmed that process is not a formality — it is the backbone of legitimacy in regulatory actions.

Insufficient Fact Base & Arbitrary Scope

The court also highlighted that basing the ban on an inspection of only 4 units out of 34 was insufficient to generalize across ONGC’s entire operational domain. The limited sample and lack of broader stakeholder input weakened the foundational legitimacy.

Further, it noted that no records showed that alternative measures were considered or impacted stakeholders consulted — making the ban appear arbitrary.

Remedy & Directions

The bench struck down the 1994 notification as void ab initio (from its inception). It directed that ONGC, if required, may now engage contract labour in the previously banned categories, subject to compliance with labor law norms. The court’s order may trigger re-tendering, outsourcing, or regularization as applicable.

However, the court left room for the Centre to revisit the matter — to issue a fresh, properly consulted notification if justified. It did not bar the government from re-instituting a ban, but mandated that any such step be done following due procedure.

Implications for PSUs, Staffing & Labor Policy

Flexibility vs. Security

One of the biggest impacts will be on staffing flexibility. PSUs often rely on contract labour for auxiliary functions, project work, and temporary surge capacity. With the ban lifted, ONGC (and possibly other PSUs) may reintroduce or expand outsourcing in functions previously off-limits.

On the flip side, the decision could put contract workers in a more favorable legal environment, as rules governing their hiring, benefits, safety and rights may now vest with more clarity and oversight.

Re-tendering & Contractor Engagement

Many PSU contracts may need to be revisited. Ongoing contracts may expire or be renegotiated. Departments may issue fresh tenders, or convert existing contractors into direct hires, depending on operational needs.

Risk for Precedent PSUs

Beyond ONGC, other PSUs bound by similar historical ban notifications—if any—may seek relief using this precedent. The judgment injects a legal lever for entities like power utilities, mining, or industrial PSUs that have faced restrictive contracting rules.

Labor Relations & Union Reactions

Unions may oppose sudden surges in contract hiring, fearing dilution of job security or bypassing of workers for permanent employment. Some may demand safeguards, retrenchment protections, or quotas. Governments will need to balance flexibility with labor justice.

Policy & Legislative Revisions

The Centre may choose to appeal to the Supreme Court. Alternatively, it may draft a fresh, consultative notification, or revise labor policy frameworks governing outsourcing in PSUs. Legislative amendments to contract labour laws could also be considered.

Voices & Reactions

“The 1994 notification was a procedural overreach; this verdict restores constitutional discipline in labor regulation,” said a labour rights lawyer in Dehradun.

ONGC officials, responding to media queries, expressed cautious optimism, noting that the judgment provides operational leeway but expects follow-up policy clarity.

Some union leaders expressed concern:

“We must ensure that contract labour is not misused to erode permanent jobs,” they said, requesting that any new contracting regime include protections for wages, benefits and continuity.

Legal observers note that if the government appeals, the Supreme Court may refine the balance between statutory process and PSU autonomy.

What’s Next: Watch Points & Implementation

- Whether the Centre appeals to the Supreme Court

- Whether a fresh notification is drafted with mandatory consultation

- How ONGC revises its staffing and contracting plans

- The response of labour unions and possible litigation or industrial actions

- Whether other PSUs file similar challenges or demand relaxation

- Whether Parliament or the Ministry of Labour reviews contract labour law in light of the judgment

Broader Significance: Rule of Law & Administrative Process

This judgment reinforces a fundamental principle: statutory procedures cannot be bypassed in favor of expediency. The ruling validates that even in matters of public sector employment, due process, consultation, stakeholder engagement and fact-based decision-making are not optional.

For India’s PSU and administrative machinery, the message is clear: policy changes — especially those affecting millions of workers — must live or die by reason, not fiat.

Concluding Thoughts

By quashing the 1994 ban, the Uttarakhand High Court has reopened the landscape of how PSUs manage labour: balancing flexibility and process, productivity and fairness, outsourcing and accountability.

The real-world impact — in ONGC and beyond — will depend on how swiftly and thoughtfully the Centre and PSUs respond. The judgment presents opportunity, but only if exercise of contracting power respects labor dignity, fairness, and transparent process.

This is not just a PSU staffing shift. It’s a reaffirmation: in labor law, legitimacy begins with procedure — and justice demands no less.

#ONGC #ContractLabour #UttarakhandHC #PSU #LabourLaw #WorkersRights #AdministrativeLaw #DueProcess

+ There are no comments

Add yours