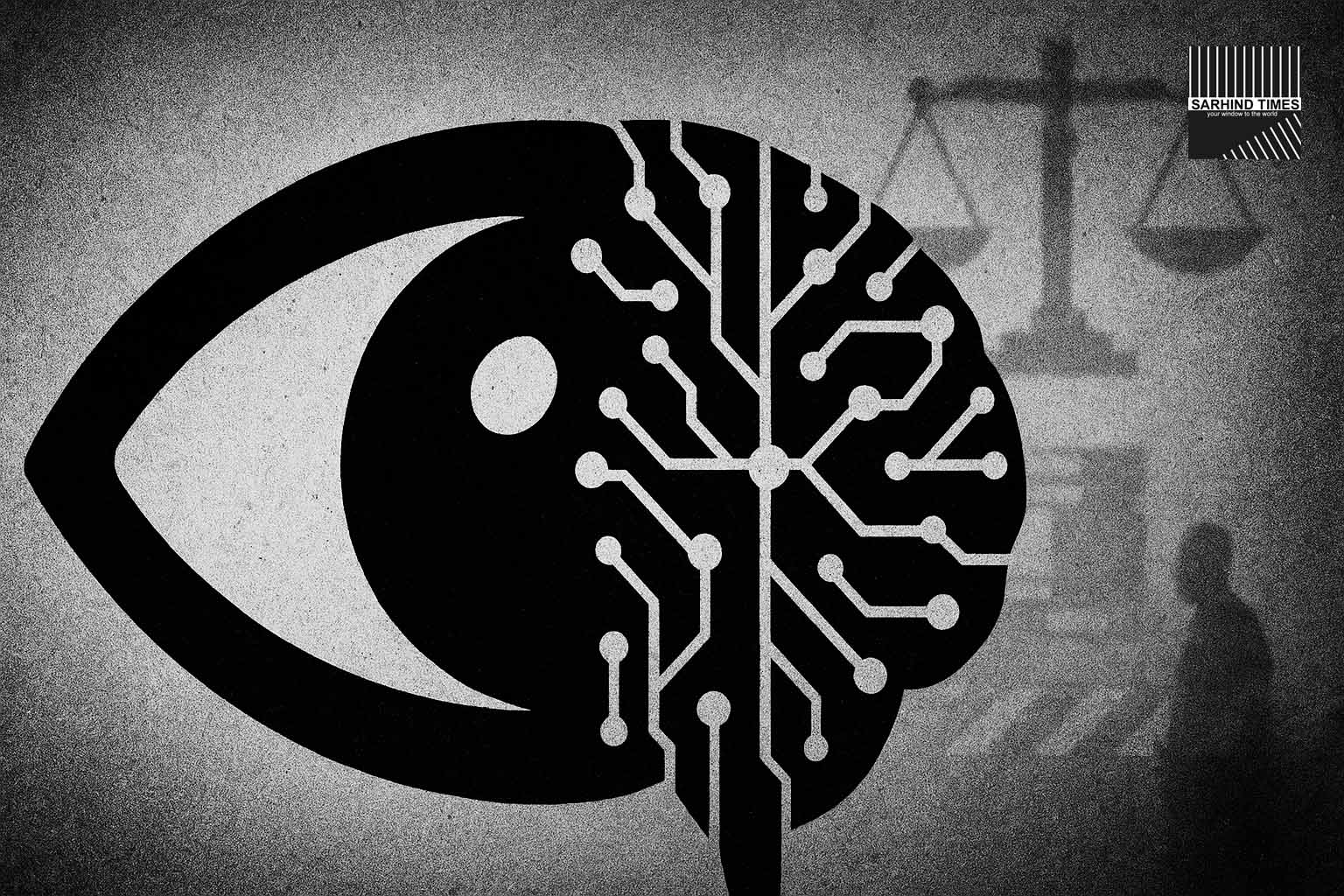

New Delhi, October 18, 2025 — In a landmark judgment, the Delhi High Court has held that “seeing” cannot be equated solely with ocular function, but must include how the brain interprets and understands visual information. This expansive interpretation may significantly loosen rigid medical disqualifications in government job recruitment, especially for persons with blind or low vision disabilities.

The judgment came in Mudit Gupta v. Airports Authority of India (AAI), where a visually impaired candidate challenged his rejection for a role in Junior Executive (Law). The court quashed the rejection, directing that functional vision and inclusive assessments should replace narrow clinical tests.

By emphasizing that the eye is but a transmitter, and that the brain performs the act of “seeing,” the court has recast departmental fitness criteria and opened the door for rethinking exclusionary practices.

Case Background & Legal Journey

Factual Matrix

Mudit Gupta, a blind candidate, had cleared AAI’s computer-based examination for the Junior Executive (Law) position. However, following a medical board assessment, his candidature was withheld—on grounds of “lack of ability to see”—despite the job being reserved under the blind / low-vision category.

Gupta challenged the rejection, along with two other similarly affected candidates. The case brought into sharp relief the tension between statutory reservation frameworks (under the RPwD Act, 2016) and medical fitness tests that exclude despite statutory eligibility.

Bench & Judgment

The Division Bench of Justices C. Hari Shankar and Ajay Digpaul heard the matters. In its reasoning, the court drew on jurisprudence from the Supreme Court’s In re: Recruitment of Visually Impaired in Judicial Services and other disability-rights pronouncements.

Rejecting a “myopic interpretation” of “seeing,” the court held that even if the eye fails to record images, if a candidate can perceive or understand visual information via assistive means, he must be considered functionally able to “see.”

The court quashed the rejection orders and directed AAI to reassess the petitioners’ candidatures with functional assessments in enabling environments and using assistive devices, rather than disqualifying on rigid medical norms.

Notably, the court refused to strike down Note 8 of the DEPwD (Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities) notification, but emphasized its interpretation and application must conform to the inclusive vision the court outlined.

The Significance & Implications

Shifting from Clinical to Functional Paradigm

Until now, recruitment rules and medical boards often equated “seeing” with retinal/macular function, discarding candidates who failed certain clinical thresholds—even if they could operate with adaptive aids. The HC’s ruling shifts the paradigm: focus on capability over limitation.

Under this framework, a candidate’s working ability to perceive, interpret, respond to visual stimuli (possibly via magnifiers, screen readers, tactile cues) becomes central. Departments may no longer reject visually challenged candidates based purely on eye health.

Inclusive Hiring & Reasonable Accommodation

The judgment harmonizes with the RPwD Act, 2016, which mandates reasonable accommodation to enable equal opportunity. The court’s approach underscores that exclusionary medical norms cannot override statutory rights.

Training, assistive tools, and job redesigns may become more common. Medical boards will need to be restructured to factor in assistive environments. Departments will be pressed to issue circulars and guidelines aligning job-fitness criteria with this broadened understanding.

Impact Across Departments & PSUs

Many government recruitment advertisements currently include vision standards for eligibility. These may have to be revised. PSUs, central agencies, police or administrative services may need to revisit their medical standards to ensure they don’t disproportionately exclude persons with disabilities.

Given that many roles rely more on reading, comprehension, and judgment than visual acuity, the expanded interpretation will likely benefit many aspiring candidates.

Potential Challenges & Pushbacks

Some departments may argue that certain posts genuinely require high visual acuity (e.g., traffic policing, field inspection). The court’s framework allows for such exceptions when the job demands particular visual capacity. The test will be whether such exceptions are justified bona fide, not as disguised exclusion.

Opponents may claim this opens floodgates of litigation or operational risks. However, the judgment provides guardrails: inclusion with context, not blanket fitment for all roles.

Comparative & Constitutional Context

Globally, disability rights jurisprudence has been evolving toward functional assessments rather than rigid medical tests. Many jurisdictions adopt models where reasonable accommodation, assistive tech, and inclusive design allow broader participation.

In India, the Supreme Court in In re: Recruitment of Visually Impaired in Judicial Services held that visually impaired persons could be considered for judicial services given effective adaptations. This HC ruling is consistent with that outlook, applying it more broadly beyond courts.

Constitutionally, Article 16 (equality of opportunity in public employment), Article 14 (equality before law), and the non-discrimination mandate of the RPwD Act provide firm grounds for interpreting fitness norms in a non-exclusionary way.

Voices & Reactions

Disability Rights Advocates

They have lauded the verdict as a progressive stride toward inclusive hiring. Many see it as a test case that could ripple across all Indian recruitment systems, cutting down arbitrary medical bars.

Legal Experts

They stress that the ruling underscores that interpretation matters. Departmental rules are not sacrosanct if their application leads to exclusion of constitutionally protected categories.

Public Service Commissions / Departments

They now face the task of revamping medical boards, job advertisements, recruitment circulars, and drafting standard operating procedures that reflect this functional vision approach.

What to Monitor & Next Steps

- How central ministries, UPSC, PSCs revise vision standards in their job ads

- Whether public sector undertakings adopt this inclusive interpretation

- Emergence of new tribunal/litigation over posts considered “vision-intensive”

- Training of medical boards in functional evaluation and assistive assessments

- Role of assistive devices, adaptive technologies, and job redesign in implementation

- Repercussions for candidates previously disqualified—possible reopenings or redress

Concluding Reflections

The Delhi High Court’s ruling on “functional sight” is more than a semantic shift—it is justice rewriting the lens through which disability and eligibility are viewed. By insisting that the brain’s ability to perceive matters more than the eyeball’s imperfections, the court has reoriented recruitment from exclusion to inclusion.

This decision reinforces a core truth: equality in law must become equality in opportunity. For many visually impaired or low-vision aspirants, it may open doors long shut. For policy makers and administrators, it mandates a rethinking of norms. The real test lies in translating this philosophy into recruitments, medical boards, training, and culture.

If executed well, it could mark a turning point in how India builds its public workforce—a more inclusive, dignified, and constitutionally faithful public employment regime.

#DelhiHC #InclusiveHiring #DisabilityRights #Law #Governance #EqualOpportunity #Accessibility #FunctionalVision

+ There are no comments

Add yours