By Sarhind Times Urban Affairs Desk

New Delhi, Sept 30

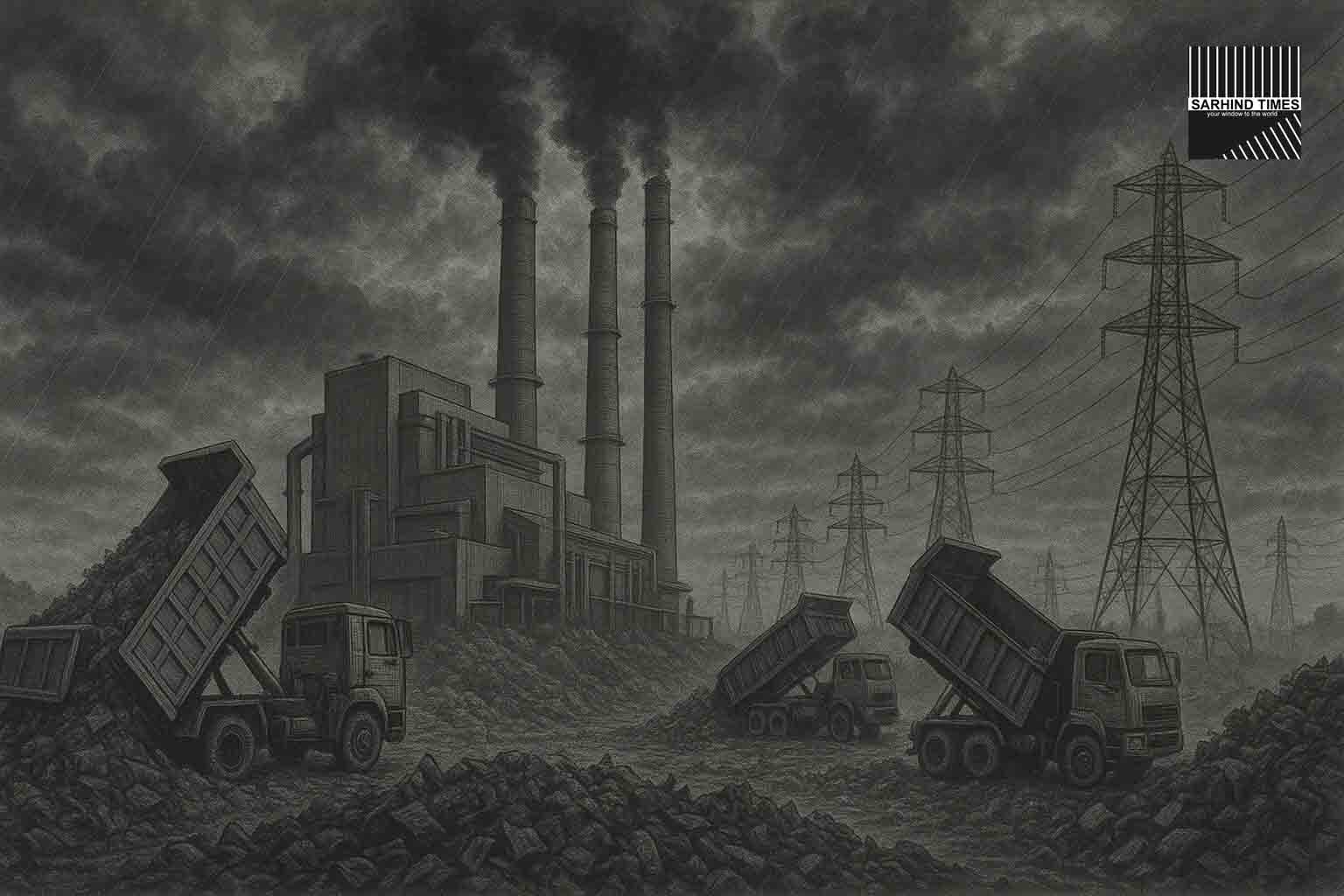

Delhi’s bid to tackle its mounting garbage crisis is set for a major push with a ₹900-crore expansion of the Tehkhand waste-to-energy (WTE) plant. The upgrade will add 20 MW of new capacity, taking the plant’s total output to 45 MW, according to officials involved in the project.

The announcement underscores the capital’s shift towards formalized processing of municipal solid waste—a move aimed at reducing the city’s overflowing landfills and capturing energy from refuse that would otherwise choke open dumps.

🚨 What the Expansion Means

- New Capacity: 20 MW addition, taking total capacity to 45 MW.

- Objective: Reduce load on Delhi’s landfills, particularly Ghazipur, Okhla, and Bhalswa.

- Technology: Controlled combustion with energy recovery.

- Cost: ₹900 crore, spread across construction, monitoring, and emission control systems.

- Timeline: Tendering and construction milestones expected over the next 18–24 months.

Waste-to-Energy in Context

Delhi generates over 11,000 tonnes of municipal solid waste daily. Currently, much of this ends up at three massive landfills—Ghazipur, Bhalswa, and Okhla—which have grown into hazardous “mountains of waste.”

The Tehkhand plant, commissioned in 2022 with an initial 25 MW capacity, was designed to process a share of this waste stream. With the planned expansion, Delhi’s cumulative WTE capacity will climb closer to 250 MW, spread across multiple facilities.

Government’s Pitch

Officials argue that the project:

- Cuts landfill dependence by diverting thousands of tonnes of waste daily.

- Generates renewable energy in line with India’s clean power goals.

- Aligns with Swachh Bharat Mission and the broader “zero landfill” vision.

- Meets CPCB norms with stack emission controls and continuous monitoring.

A senior urban development official told Sarhind Times:

“This expansion is not just about producing more megawatts. It’s about reducing Delhi’s waste burden, improving urban health, and making our city cleaner.”

Concerns and Criticism

Environmental campaigners and residents’ groups remain skeptical. Their concerns include:

- Air Pollution: Stack emissions, even when controlled, can contribute to particulate load in an already polluted city.

- Ash Disposal: Fly ash and bottom ash management often lags behind, creating secondary hazards.

- Segregation Shortfalls: WTE plants rely on high calorific-value waste; poor segregation at source means plants often burn mixed garbage, releasing toxins.

Activists have repeatedly asked for greater transparency in emission data, third-party audits, and parallel investments in segregation and composting.

Complementary Measures

To address critics, civic bodies stress that WTE is one part of a multi-pronged strategy:

- Segregation at Source: Public campaigns to separate wet, dry, and hazardous waste.

- Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs): Sorting recyclables before incineration.

- Biomethanation Plants: Converting organic waste into biogas.

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): Holding companies accountable for plastic waste.

Officials say these systems, working alongside WTE, can minimize environmental impact.

Impact on Communities

The expansion will directly affect neighborhoods near Tehkhand:

- Traffic: More trucks ferrying waste could mean congestion.

- Air Quality: Residents demand real-time emission dashboards.

- Noise & Odor: Daily plant operations raise quality-of-life questions.

Civic leaders argue that strict regulation, green belts, and monitoring systems can mitigate these impacts.

National & Global Comparisons

- India: Delhi, Hyderabad, Pune, and Indore lead in WTE deployment.

- Global: Cities like Copenhagen, Singapore, and Tokyo showcase advanced WTE facilities integrated with district heating and public parks.

Delhi’s challenge is to replicate global best practices in emission control and community engagement.

Climate & Sustainability Lens

Waste-to-energy is often positioned as renewable, but experts point out:

- Carbon emissions remain significant, though less than methane from landfills.

- Circular economy models prefer recycling and composting over incineration.

- Net impact depends on strict segregation and technology performance.

Still, in a city drowning in garbage, WTE remains a pragmatic—if imperfect—tool.

Conclusion

The ₹900-crore expansion at Tehkhand reflects Delhi’s attempt to balance waste management, urban planning, and sustainability. While WTE plants cannot be the only solution, they remain a critical stop-gap for a city struggling with overflowing landfills.

The real test will be in execution—ensuring that promises of cleaner emissions, effective ash management, and robust segregation are met. Only then can Delhi move from being a city of garbage hills to one of clean energy and circular economy practices.

#Delhi #WasteToEnergy #UrbanInfra #Sustainability #CircularEconomy #CleanIndia #Pollution #MunicipalWaste #ZeroLandfill #ClimateAction

+ There are no comments

Add yours