India’s coffee heartland—Kodagu, Chikkamagaluru, and Hassan—is at a crossroads. For decades, these lush districts of Karnataka have been synonymous with rich Arabica and Robusta beans, supplying not only domestic demand but also fueling international markets. Now, with the European Union’s new Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) set to take effect on January 1, 2026, growers are bracing for a wave of uncertainty.

The regulation requires that any coffee exported to the EU must be certified as “deforestation-free,” backed by precise geolocation and polygon mapping of plantations. For India, where 70% of coffee is exported and nearly 60% heads to Europe, this is more than just a compliance issue—it’s an existential challenge for thousands of smallholders.

What the EUDR Means

The EU’s Deforestation Regulation is part of Europe’s broader climate and sustainability commitments. It targets commodities linked to deforestation, including coffee, cocoa, soy, palm oil, cattle, and timber. Exporters to the EU will need to:

- Prove that their goods are not sourced from land deforested after December 31, 2020.

- Provide geolocation coordinates of each plantation or polygon mapping to establish traceability.

- Submit due diligence statements confirming compliance.

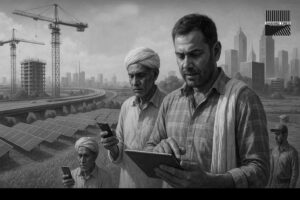

For smallholder farmers in Karnataka, many of whom manage 2–5 acre plantations, the requirements present daunting logistical, technical, and financial hurdles.

Karnataka’s Coffee Belt at Risk

Karnataka contributes over 70% of India’s coffee production, with districts like Kodagu known for their shaded plantations, biodiversity, and intercropping practices. While larger estates are equipped to adapt to certification norms, small and medium growers face disproportionate risks:

- Lack of Digital Tools: Many farmers still rely on traditional land records rather than GPS-enabled mapping.

- High Certification Costs: Independent audits and mapping can cost more than smallholders’ annual profits.

- Risk of Exclusion: Exporters may bypass uncertified farmers, consolidating procurement through large estates.

- Price Penalties: Those unable to comply may be forced to sell at discounted rates in non-EU markets.

One grower in Chikkamagaluru remarked:

“We are not cutting forests to grow coffee. Our farms are generations old, with trees that support birds and wildlife. Yet we are being asked to prove our innocence through expensive technology we cannot afford.”

Coffee Board’s Response

The Coffee Board of India has acknowledged these concerns and is taking steps to cushion the impact:

- Enhancing the India Coffee App to allow farmers to register plantations digitally.

- Deploying extension officers to assist in mapping farms and training growers in compliance protocols.

- Exploring government subsidies to offset certification costs for smallholders.

- Engaging with EU counterparts to negotiate flexible timelines and support measures.

According to Coffee Board officials, the objective is to ensure that no farmer is left behind. However, bureaucratic delays and limited outreach have left many growers anxious.

Potential Economic Fallout

Failure to comply with EUDR could be catastrophic:

- Market Losses: EU buyers account for nearly $700 million annually in Indian coffee exports. Losing this access would severely dent revenues.

- Global Competitiveness: Countries like Brazil and Vietnam, with stronger institutional frameworks, may corner markets if Indian producers lag.

- Domestic Oversupply: If exports shrink, domestic markets may face glut conditions, depressing prices further.

Sustainability vs. Reality

Ironically, many Indian coffee plantations—especially in Karnataka—already embody sustainable practices. Shade-grown coffee intercropped with pepper, cardamom, and fruit trees contributes to biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

Yet, the one-size-fits-all compliance mechanism of the EU may penalize these very farms. Environmental advocates stress the need for localized certification models that recognize India’s unique plantation ecology.

Policy Recommendations

Experts suggest several interventions to safeguard farmers’ livelihoods:

- Subsidized Certification: Government schemes to cover mapping and audit costs for smallholders.

- Cluster-Based Compliance: Group certification for village-level clusters to reduce costs.

- Technology Partnerships: Collaborations with tech firms for affordable GPS mapping and blockchain traceability.

- Diplomatic Engagement: Negotiating transitional arrangements with the EU for gradual implementation.

- Awareness Campaigns: Training farmers through cooperatives and extension networks.

Farmers’ Voices

- Smallholder, Hassan:

“We fear being left out of global trade. Without support, many of us may have to abandon coffee.”

- Estate Owner, Kodagu:

“Large estates can comply, but the soul of Indian coffee lies with smallholders. If they are excluded, the diversity of our beans will vanish.”

Conclusion

The EU’s Deforestation Regulation may be well-intentioned, aiming to safeguard global forests, but its rollout threatens to upend the lives of thousands of Karnataka’s coffee farmers. Unless immediate steps are taken to bridge the compliance gap, India risks losing not just market share but also the cultural and ecological legacy of its coffee belt.

For India, the challenge is two-fold: protecting farmers’ livelihoods while aligning with sustainability-driven trade norms. The outcome will determine whether Indian coffee continues to thrive on the global stage—or becomes a casualty of regulation.

+ There are no comments

Add yours