Dateline: GURUGRAM | Monday, October 6, 2025

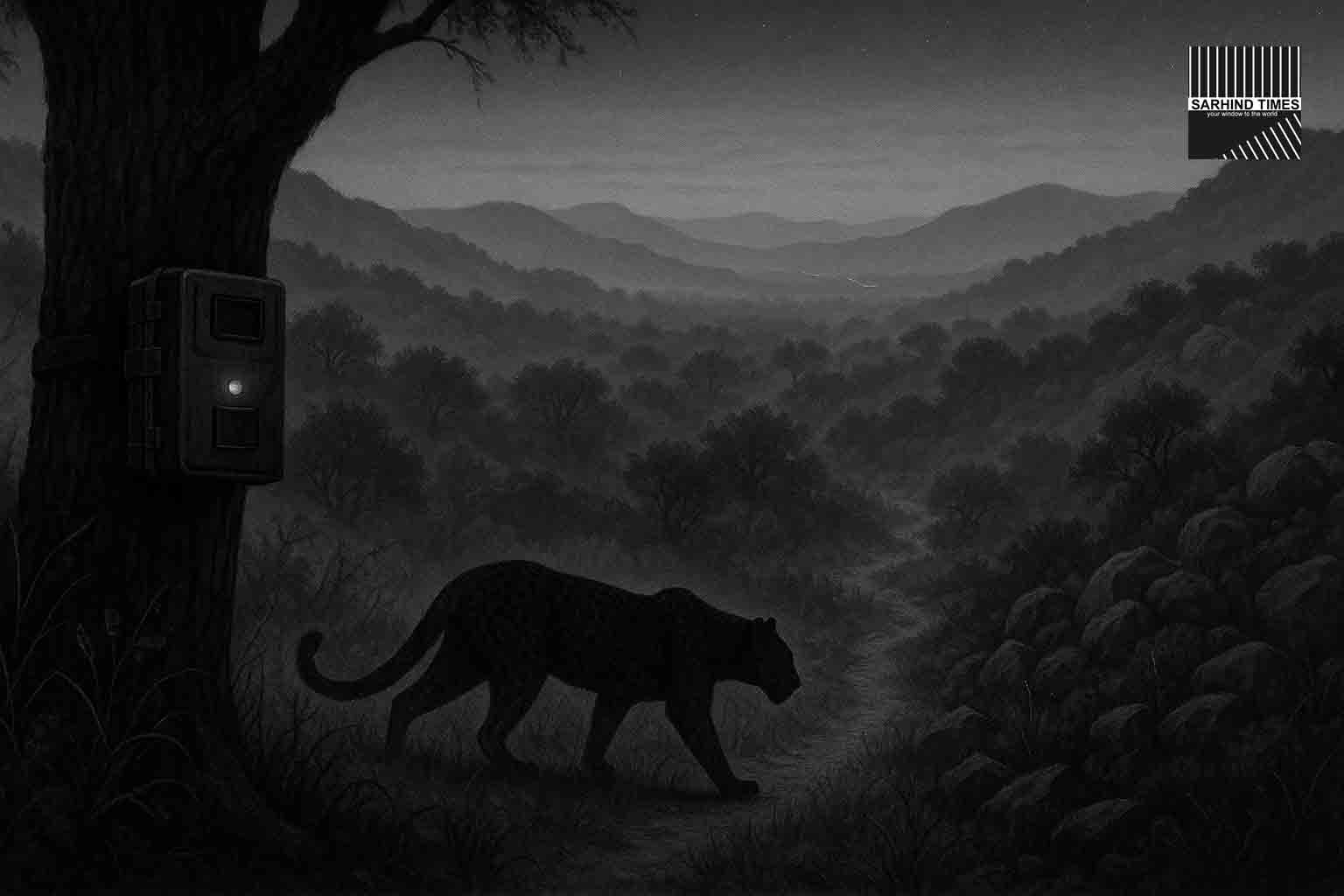

The Aravalis are stirring before dawn. Along the rocky scrub of Mangar Bani—NCR’s last primary forest—rangers are bolting steel camera housings to trees, checking batteries, and aligning sensors with animal trails. Over the next several months, 64 camera traps will watch silently from Surajkund in Faridabad down to Damdama in Gurugram—a landscape of roughly 15,000 hectares. The goal: a high-resolution census that shows not just what is there, but how it moves through a mosaic of villages, quarries, highways and farms. Preliminary results are due in early 2026 and will feed straight into corridor planning and on-ground mitigation.

What makes this effort different from earlier, sporadic surveys is its grid discipline—devices deployed in 5×5-km blocks, cycled for 30–45-day intervals, with a handful left in place for long-term signals. That rigor is by design: in the northern Aravalis, wildlife survival hinges on connectivity—threads of habitat that stitch together sanctuaries like Asola Bhatti and larger reserves in Rajasthan.

Why Mangar Bani matters—right now

The Aravalis look hardy, but their ecology is delicate. In just a decade, roads, real estate, and quarry scars have pressed closer to the ridges, pinching the paths that animals use. Camera-trap research between 2022 and 2024 found that leopards still occupy a striking 85% of the Gurugram–Faridabad Aravalis, sharing space with striped hyenas, nilgai and jackals; rarer presences—rusty-spotted cat and elongated tortoise—were also logged. The takeaway was sobering: wildlife persists, but amid intensifying human pressure.

Recent incidents have underscored the risk at the edge where forest meets asphalt. In late August, a young female leopard was found dead on the Gurugram–Faridabad road, triggering fresh calls to keep high-speed traffic and wild movement apart. Authorities have since floated RCC barrier walls for collision-prone stretches and linked plans for wildlife underpasses—a package that will be informed by the very movement data these 64 cameras are meant to deliver.

The study: how 64 lenses can see a living landscape

The grid. Teams are laying out a checkerboard of sites across Mangar, Dauj, Pali and Damdama. Each camera is placed along game trails, ridge saddles, drainage lines or “pinch points” where animals are likely to pass. Overlapping fields of view allow for “recapture” of individuals and help model occupancy and movement with fewer blind spots

The cycle. Cameras will run in 30–45-day cycles, then be rotated to the next set of grids. A smaller cohort will remain as semi-permanent stations to detect seasonal or year-to-year shifts. This “rolling panel” gives both breadth (many places sampled) and depth (some places watched continuously).

The output. Expect three layers of insight:

- Presence/occupancy—which species appear in which grids and how often;

- Pathways—preferred ridgelines, streambeds and culverts;

- Hotspots & hazards—places where movement intersects roads, settlement edges or construction. Those layers then inform where to put speed-calming, animal signage, culvert retrofits or future underpasses—measures that can sharply cut collisions with large mammals like leopards and nilgai.

The basecamp. Authorities have proposed a mini wildlife monitoring & research centre at Mangar or Dauj—a hub to house data, train frontline staff, and anchor continuous monitoring rather than one-off studies. That institutional memory is what turns a survey into a long-term program.

Beyond counts: corridors, choke points and fixes

Corridor logic. From the Delhi ridge to the Sariska landscape, the Aravalis function as a chain. Break a few links and the chain stops moving. The camera program will validate “folk maps” that residents already know—where animals cross streambeds, skirt the back of villages, or slip under culverts when traffic thins. Those paths, once confirmed, can be protected and made safer with a menu of options: underpasses, retro-fitted culverts with natural substrate, vegetation buffers, fencing or channelling near highways, smart signage, and average-speed enforcement on critical road segments. Recent state proposals for RCC walls on parts of the Gurugram–Faridabad and Gurugram–Manesar roads sit within this debate—the cameras will help test where barriers make sense and where connectivity must be engineered underneath the tarmac.

Drones and transects. Parallel exercises—drone flights, line transects, and vegetation plots—are already planned to cross-check the camera-trap story. Each method sees something different: drones can scan edges and new clearings; transects pick up livestock pressure and human use; vegetation plots show habitat quality. Together they will locate the few remaining “must-keep” corridors across the Haryana Aravalis.

What the leopards are telling us

Leopards are adaptable, but they also suffer the costs of our proximity. The 2022–24 study that mapped 85% occupancy also recorded a flood of images of humans and livestock, signalling intense overlap. Rare species sightings—rusty-spotted cat, sambar, elongated tortoise—are heartening, but they also emphasize how unique Mangar-to-Damdama remains within NCR. The new camera network should update that ledger with finer time-stamps and micro-routes: where leopards cross at 2 a.m., how hyenas skirt wall lines, where nilgai hesitate at bright motorcycle clusters. Those “small maps” are the blueprint for targeted fixes.

The human angle: villages, roads and livelihoods

Mangar Bani is not a remote jungle—it is a lived-in landscape. Villages, farms, shrines and picnic spots sit within minutes of leopard habitat. That proximity brings pride and friction. Community organisers and naturalists have spent years recasting Mangar—from “scrubland” to living classroom and heritage forest, a shift that has nurtured local guardianship. Yet roads cut through, and weekend traffic surges. In such a setting, data-led design—slower approaches near known crossings, better night lighting only where appropriate, clear signs, and quiet culverts—can improve safety without turning the forest into a fortress.

Law, policy and the Aravalis’ legal grey

Several conservation groups have urged clearer legal recognition for Mangar Bani and its contiguous commons. Researchers warn that ambiguities around “deemed forests” and rapid land-use change could unravel coexistence within a decade if not addressed with enforceable protections and properly engineered infrastructure. The corridor science from this camera-trap project will be ammunition for that policy fight—maps and images tend to move committees faster than adjectives.

Roadkill is data too

The leopard roadkill in late August concentrated attention on a simple truth: a single highway can sever generations of safe passage. Each collision is a data point—date, time, location, weather, traffic speed. Fold these into camera-trap detections and a pattern often emerges: a curve with early morning crossings, a culvert animals avoid due to standing water, an exit ramp with blinding glare. The project’s success will be judged not only by a species list but by the number of engineered, measurable risk reductions it triggers by 2026.

Science notes: what cameras can (and can’t) do

- They see, but don’t explain everything. A blank camera and a full memory card can mean the same thing—placement, weather, human disturbance or sheer animal whim. That’s why multiple grids and repeated cycles matter.

- Species differ in “camera-friendliness.” Hyenas and nilgai often use trails; small cats may hug undergrowth. Expect the dataset to over-represent some species, under-represent others.

- Cameras start the conversation. The fixes—underpasses, culvert retrofits, speed control—are engineering and enforcement problems. Drones and ground transects help fill the gaps.

Heritage underfoot

Mangar is more than biodiversity; it’s deep history. Archaeologists have documented Lower Palaeolithic tools here, reminding us these hills have shaped—and been shaped by—humans for hundreds of thousands of years. Any plan that restores corridors is also, in a quiet way, restoring continuity with that past.

What to expect through 2026

- Q4 2025–Q1 2026: Camera rotations across all grids; interim species occupancy maps; identification of top 10 crossing hotspots needing civil works.

- Early 2026: Preliminary report and corridor atlas; proposals for underpasses, culvert retrofits, and vegetation buffers submitted with costings.

- Parallel: Tendering and pilot works on priority road segments along the Gurugram–Faridabad corridor—barriers where necessary and permeability engineered under the road.

How residents and commuters can help

- Slow where the hills begin. Average-speed enforcement works, but driver choice is faster.

- Report sightings responsibly. Share time and precise location with the forest helpline; avoid crowding animals for photos.

- Back underpasses, not walls alone. Barriers may be needed at some spots, but safe crossing structures keep landscapes whole.

- Support citizen science. Local walks and clean-ups have built pride and watchfulness in Mangar—participation keeps pressure for better design alive.

Key Numbers (at a glance)

- 64 camera traps across Mangar–Dauj–Pali–Damdama grids, cycling every 30–45 days; a few will be permanent.

- ~15,000 ha study landscape from Surajkund to Damdama.

- 85% leopard occupancy (2022–24 study) in Gurugram–Faridabad Aravalis; rare records include rusty-spotted cat and elongated tortoise.

- Leopard roadkill (Aug 30–31) focused attention on crossing risk near high-speed corridors.

+ There are no comments

Add yours